Milan

When Silvio Berlusconi’s empire finally began to crumble around him in 2011, The Economist magazine ran a headline which captured the zeitgeist. It read: ‘The man who screwed an entire country’. One of the few exceptions to that statement would be rugby in Amatori Milan, which thrived under his patronage in the 1990s. That is, unless he turned up to watch.

Massimo Cuttitta watched the first match of his country’s Six Nations campaign in his small room in the attic of his mother’s house in Latina, an intimate city in Lazio, 40 minutes south of Rome by train.

This was not the original plan for the 54-year-old former Italian prop. Ever since Italy joined up with the Five Nations in 2000, he’s become accustomed to watching the opening game of the Gli Azzurri in a different setting. “We always watch the first game together,” he explains. “Almost all the players who played together in the Milan rugby team meet before Italy’s first game in the Six Nations. “It’s one of the happiest moments of the year,” he continues. “We eat together before, drink together during the game and, usually, are disappointed to see our team’s result.”

The last part was, at least, consistent this year as Italy, in front of empty stands at the Stadio Olimpico in Rome, were defeated 50-10 by France. Massimo takes a deep breath. “It absolutely should not have looked that way,” he says painfully of his team’s lack of achievement. “It’s very sad,” he reiterates. “We are the generation that created the rugby breakthrough in the country. The team created by Silvio Berlusconi in Milan in the 1990s paved the way for the golden age of the game in Italy.

“We reached tremendous heights – who ever dreamed we’d join the Six Nations? – but sadly the captain of the game in Italy did not know how to leverage our achievements. They did not know how to build a new generation of players that would continue the tradition we have created.”

Just over five years ago, Massimo – who played 69 times for his country from 1990 to 2000 – returned to Italy after a number of years in the UK, where he’d been working with Andy Robinson, first at Edinburgh and then with the Scottish national side, a role he also carried out for Scott Johnson and, lastly, Vern Cotter.

Since his return, he’s advised on the scrums of both Romania and Canada, and his latest role, with Portugal, was due to begin during lockdown so, like many coaches, his duties have been carried out via Zoom.

There have also been more important matters to deal with. “The years go by and mum doesn’t get any younger,” he says. “The first days of the epidemic were terrible. The death toll in Italy was enormous. My brother [Marcello, also an Italian rugby international, but with 54 caps on the wing] and I had no doubt: we are not leaving our mother’s side. We are helping her just as she has protected us all her life.”

They say and do: the Cuttitta twins share their time on frequent trips with their mother for routine checkups with various doctors. They do not give up on her, not even for one moment.

The WhatsApp group Amatori Rugby Milano also keeps both brothers busy. There are more than 100 members in the group dedicated to their former club Amatori Milan: past players, coaches and fans. And every member asks after the well-being of Mama Cuttitta, it’s a support group in every sense, and it goes far beyond the recent pandemic. It even traverses the world, with ex-Argentina scrum-half Fabio Gómez, who won nine caps and appeared in the inaugural Rugby World Cup, also part of the group. Fabio won three Italian championships with the side alongside the Cuttittas. “We are here for each other,” explains Fabio from his Buenos Aires home. “Whenever any of us need help, he knows he has someone to talk to. Milan’s rugby team may be long dead, but the memories will stay with us forever. Although I live in Buenos Aires, I feel like I did not leave Milan. We never stopped being in touch.”

Amatori Milan were the Real Madrid of Italian rugby. Or, rather, the AC Milan of Italian rugby, in every sense. They had their own Gullits, Rijkaards and Van Bastens, they had success and, significantly, they also had the same owner.

In seven years, they won four Italian titles, finishing second twice, and now, almost a quarter of a century has passed since the sinking of Italy’s rugby flagship – the team that laid the foundations for professionalism in Italy, that helped pave the way for their Millennium entry into the Six Nations.

The Van Basten of the team was Australian. “There’s not a week goes by that I do not remember those days,” recalls former Wallaby David Campese, who joined them in 1989, aged 27.

Campese joined a side full of rugby galacticos: his old friend Mark Ella, and Italian stars such as Franco Properzi, Massimo Giovanelli, Pierpaolo Pedroni, Giambattista Croci, Massimo Bonomi, Alessandro Ghini, Diego Dominguez and, of course, the Cuttitta twins. Basically, the best of Italian rugby: “I came to Milan at an advanced stage in my career and at first I never thought about the impact this period would have on my life,” Campese says. “But those were wonderful years, full of accomplishments and experiences. Almost all the players have become my little brothers. What I am particularly proud of is the creation of culture: this team laid the foundation for the development of rugby in Italy.”

It’s remarkable still to think that the man playing a central role in all of this was the notorious Silvio Berlusconi. For any tale involving the former Italian Prime Minister and TV mogul, it’s hard not to get lost in the back story. His was one of the most megalomaniacal and fantastic sporting experiments in the country’s history.

Over the years, sex scandals and corruption lawsuits have been linked to Berlusconi’s name. In June 2013, he was sentenced to seven years in prison after a court in Milan convicted him of soliciting a minor for prostitution and exploiting his senior position to put pressure on the police. A year later the conviction and sentence were overturned by the Court of Appeals, but Berlusconi’s rule in the country may be remembered as a never-ending collection of corruption scandals alongside his uncompromising admiration for Russian President Vladimir Putin.

But in the mid-1980s, Silvio Berlusconi was a young millionaire who had amassed his fortune as a real estate entrepreneur a decade earlier. He was a major innovator in another field: the beginnings of commercial television in Italy were recorded exclusively in his name. In 1978 he bought a small TV channel, TelaMilano 58, along with a number of other broadcast frequencies, then merged them and began broadcasting to the entire country.

The success was dizzying. Berlusconi began selling commercials and even acquired the broadcasting rights to the hit American TV shows Dallas and Dynasty. These soap operas brought the American hedonism of the Ronald Reagan era to Italy.

In 1984, a court in Italy shut down his television stations because, at the time, a private person was banned from broadcasting nationwide, but he survived thanks to then-Prime Minister Bettino Craxi, a personal friend of Berlusconi and his political ally, signing three laws that allowed Berlusconi to re-broadcast and, in fact, qualified his actions.

Revenue from advertising grew, Berlusconi became a billionaire and he brought stars like Barbra Streisand and Rod Stewart to Italy, even trying to replicate the local success with the launch of TV channels in France and Spain.

But, dragging this runaway narrative back to sport, on the same day that Berlusconi inaugurated his TV channel in France, he embarked on a new adventure in Italy and acquired the AC Milan football team. Veteran manager Adriano Galliani remembers Berlusconi’s impressive entry into the club. “Three planes flew into the stadium and football stars jumped from them to the pitch,” he recalls. “I remember that well. The date was July 18, 1986. The background music was from the movie Apocalypse Now.”

Former England football boss Fabio Capello would play a key role in the AC Milan story. “I think Berlusconi’s goal has always been to reach the most senior positions and the greatest influence on the public,” he says. “I think Berlusconi was very much influenced by American capitalism and tried to create a similar franchise in Italy.

“He understood that AC Milan is a brand, something like the LA Lakers in the NBA.”

Two years after beginning the journey to turn AC Milan into the greatest football team on the planet, Berlusconi turned to rugby, purchasing L’Amatori Rugby Milano. “He wanted Milan to be number one in the world in all sports,” explains Capello.

The young Capello, then in his early forties and a former AC Milan player, was appointed to head the ambitious venture: Polisportiva Milan, or by its other name POL Mediolanum. The goal was, alongside the football club of course, bringing together in a single company, under the very famous Milanese insignia, the teams of different sports played in the city of Milan: baseball, ice hockey, volleyball and rugby.

The respective teams, initially all sponsored by the Mediolanum brand, quickly reached the highest national and international levels thanks to huge investments and the commitment of some of the leading exponents of their disciplines.

Berlusconi would shape the modern history of Italian rugby when he took over Amatori Milan, with the following ten years being the most successful in its history. Guy Pardiès, led the team as coach for the first two seasons under the umbrella of Polisportiva Milan and marched it twice to the Italian club championship semi-finals.

“It was clear that something big was happening here,” he recalls. “Although in my time we did not win the Italian Championship, the progress was amazing and thanks to players like Tim Gavin and David Campese, who came with a huge experience from Australia, new standards of coaching and commitment were created at the club.

“When you see Campese not giving up, working out in the gym, briefing the young players, you realise from the inside that a fundamental change is starting to take place here.”

Renato Benedetti, now president of Amatori Rugby Junior, recalled the fundamental change that took place in those years in the city: “It was an amazing attraction. Lots of young people, who now form the infrastructure of rugby fans in the country, began to get acquainted with the game in those years.

“Not all sports fans connected quickly, but many of them could not remain indifferent to the team. The players were cordial and human, they felt like pioneers and ambassadors of the game in the country. It was important for them to get fans to the stadium. It really comes as no surprise to me that of all the crazy ventures Berlusconi has concocted, the rugby team was the last to fall. A real and stable infrastructure of fans has been created here.”

In 1990/91 the team won its first modern title, more than 40 years after its previous one in 1946. In the final game they defeated Benetton Treviso, 37-18.

“It was crazy excitement because we knew we were doing something big,” says Campese. “It was clear to everyone that this was just the beginning.”

“Those were the best years of my life,” agrees Federico Williams, a single cap international full-back. “I joined this team at the age of 23. To come to a city like Milan, to play in a team that is actually the Harlem Globetrotters of the game is an amazing thing. It was the first time that a rugby team gathered into it all the best players in the country.

“The impact of this team on the game was far greater than one might imagine,” continues Federico. “We brought the idea of professionalism to rugby. It was a great honour to belong to such a thing. I knew in real time that we were making history.”

By 1996 the team had won four titles, every time facing Benetton Treviso in the final: a 41-15 win in 1993; a 27-15 win in 1995; and, in what was to be their last-ever title, a 23-17 victory in 1996, having trailed 9-17 at the end of the first half.

But then, something started to go wrong. Word had spread that Berlusconi had decided to give up the ambition to conquer Europe through the Milan sports teams. “One day I got a phone call and the person on the other end invited me for a personal call with Berlusconi,” recalls Marcello Cuttitta, who was then captain. “There was a lot of tension among the players, and of course with me as their representative, I was very scared of what I was going to hear.”

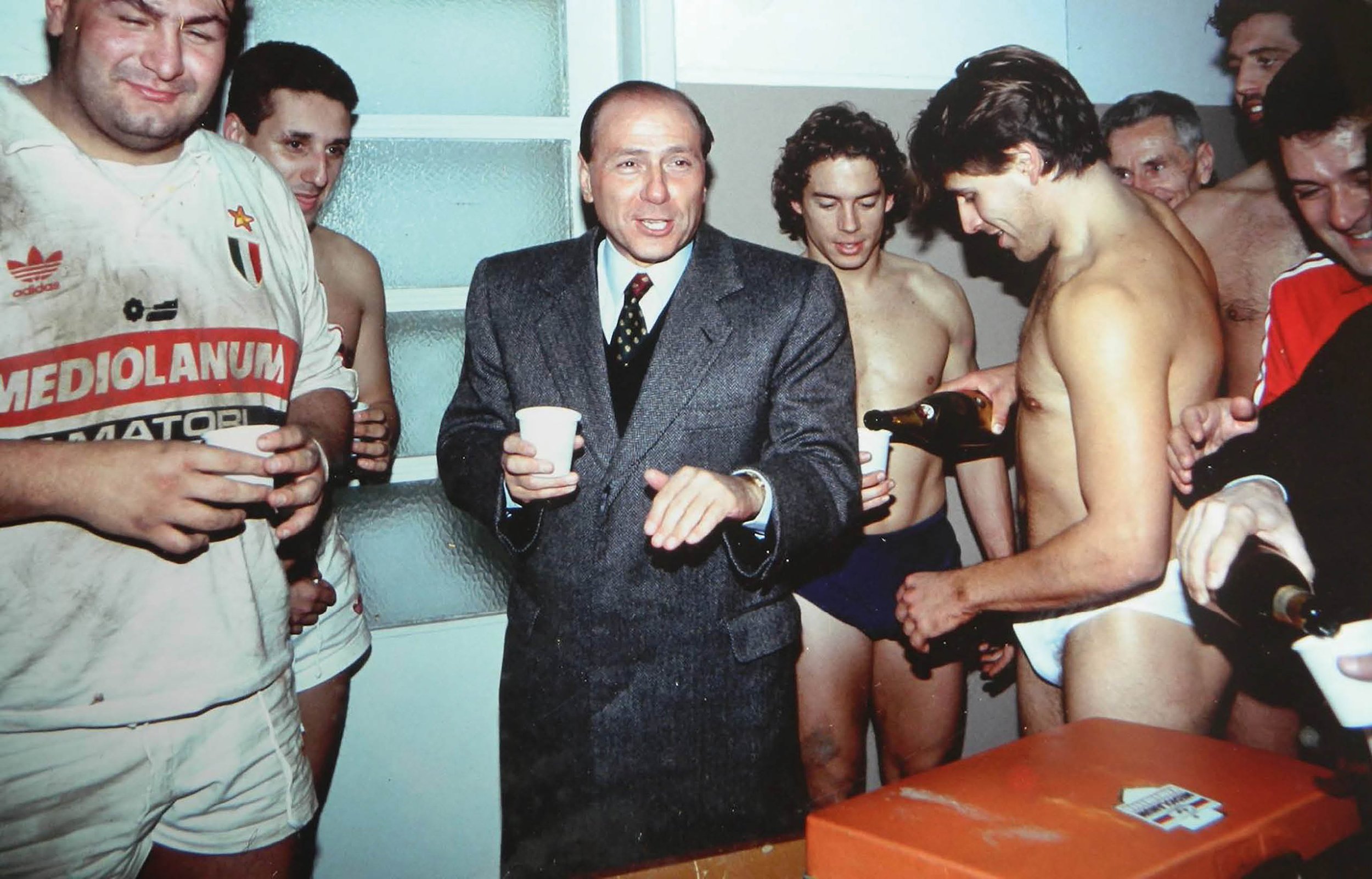

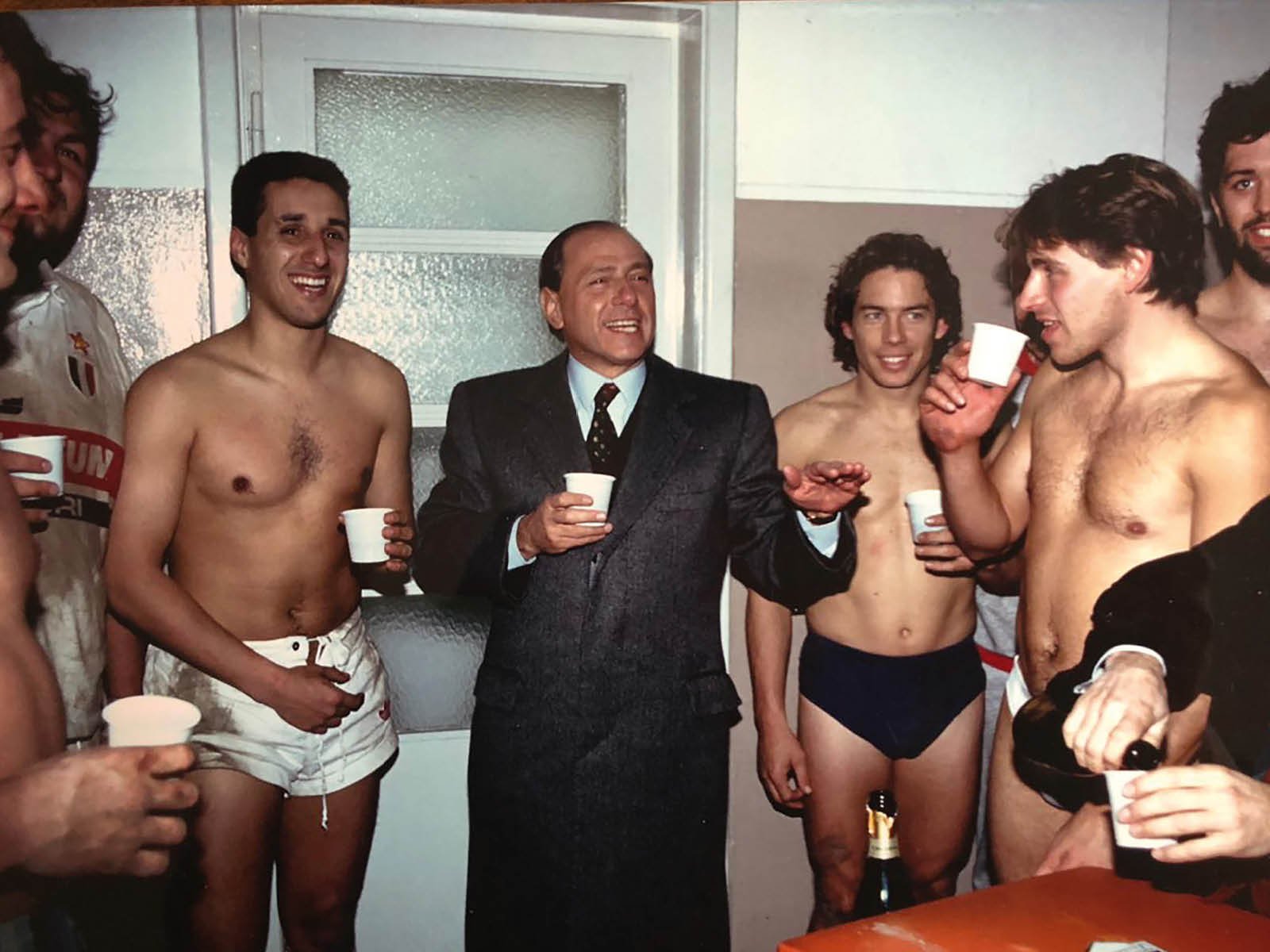

The only hope for the players was the fact that the owner had a special sympathy for the rugby team. “Unlike the other teams he managed, and was barely interested in, Berlusconi fell in love with rugby and our team,” says Federico. “He came to the games, went into the locker rooms, invited us to visit his house from time to time and gave us a feeling that there was no difference between us and the football team players who were megastars. The only problem was that every time we came to visit him, or when he came to watch us, we lost.”

The previous summer – 1995 – David Campese had returned to Australia and the legendary Italian fly-half Diego Domínguez had recently joined Stade Français, so the signs were ominous for Marcello’s conversation with the owner. “Although he told me to tell the players that he did not intend to leave the club straight away, at the same time he stated that he intended to fund the team for only one more year, until the end of the 1997/98 season.” The news came as no surprise. In fact, the players were happy just to get the extra season.

“We greatly appreciated this gesture,” explains Marcello. “It gave many players time to find new clubs, but it was heartbreaking. The dream was over.”

Amatori Milan had at least outlasted most of Berlusconi’s sporting clubs. “The association [that oversaw all of the sporting sides] was in fact dismantled in 1994,” explains Capello. “The budgets had been cut due to the poor economic results achieved by most of the teams – they were unable to cope with the massive investments made.”

But, like Amatori Milan, silverware won on the field was never in short supply. “Those teams won titles in Italy and Europe,” says Capello. “At the same time, the fact that he failed to take over the city’s basketball club, Olympia Milano, caused Berlusconi to close out the other teams, focus only on the football team, and continue modest support only for the rugby team.”

When the modest support came to an end, so too did Amatori Milan. After Berlusconi left, the team merged with Calvisano and, for several seasons played in the Italian first division as Amatori & Calvisano. Then, in 2002 a number of former players at the club, led by Massimo Giovanelli and Marcello regained the rights to use the name Amatori exclusively and began competing as an independent team in Serie C.

Marcello coached the side and the club may not have returned to the highest echelons, but they did stir an interest from their Milanese fan base.

“In the first season we managed to qualify for Serie B and you could feel that the love for the game did not disappear from the city,” he says. “We had a strong and supportive fan base that accompanied us to all the games, even in cities many hours away from Milan. During my time as Amatori’s coach we twice reached the final of the playoffs for promotion to Serie A, but unfortunately we were not able to make the extra move.”

In the summer of 2008, the team merged once again, this time with the rugby club from the city of Leonessa. The team, now under the name Amatori Rugby Milano 2008, reached Serie A, finishing seventh, but again sustainability proved beyond them.

A year later, the team ran into an economic crisis, lost much of their squad and were relegated to Serie B.

The final curtain fell in October 2011. After the club had cancelled too many games due to a lack of players, the Italian Rugby Federation excluded the team from the championship. Since then, despite various attempts, the team has failed to rise again.

And so for now, Amatori lives on in the honours’ lists and the memories and WhatsApp group of those former players and lifelong friends. “I have no doubt we had the potential to be the biggest club in the history of modern rugby,” concludes Diego Domínguez, also a member of the group. “Unfortunately, it ended earlier than expected, but at least we gained the friendships. Even from a distance, my friends from the days in Milan are still the best friends I have and have ever had.”

Massimo Cuttitta, from his room in the attic, can only agree: “It was indeed a wonderful time, creating friendships that continue to this day, but I am very sad that this team is gone,” he says. “I think we managed to create insane momentum for the game in Italy in the 1990s.

“Honestly, do you think anyone would have dreamed of the Italian team joining the Six Nations without the resonance that our team provoked? I think you have to be really naive to think it happened by chance.

“What makes me especially sad is that I still feel the hunger of the public in Milan for the team and for the game. These days can come back. I really believe in it, but it needs desire and investment. I have no doubt that the generation of players that has grown with me will be happy to give a shoulder and help.”

Story by Itay Goder

This extract was taken from issue 13 of Rugby.

To order the print journal, click here.